Dysart Station’s Officer in Charge Michael Board is still enjoying his 30-plus career but more recently, his sights have been set on recording our history using the very latest photographic technology.

While he continues to enjoy a 30-plus year career with QAS, our History and Heritage team has harnessed his extraordinary photographic skills to lay the foundations for a future 3D online viewing experience of the QAS Wynnum Museum.

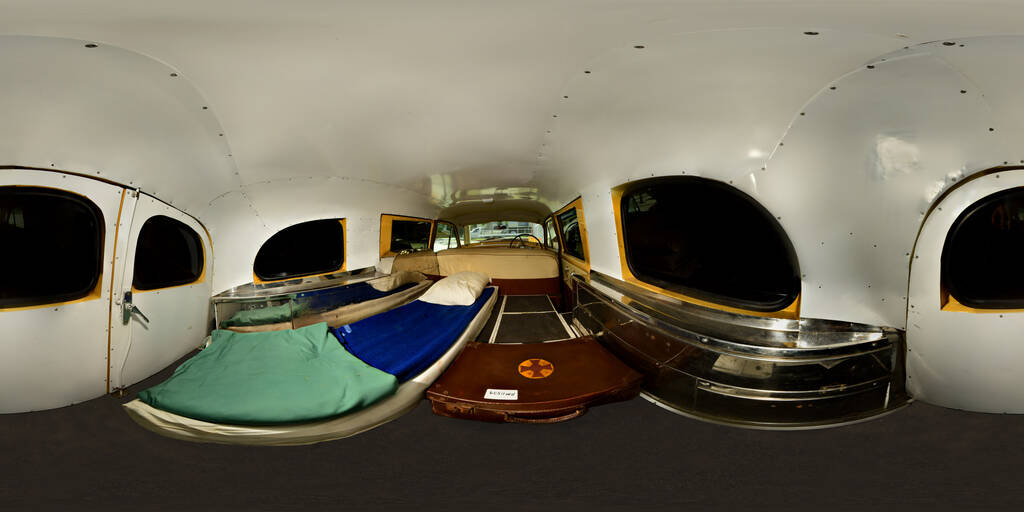

Over the last year, Michael has amassed hundreds of volunteer hours to deliver an “historic first” for our History and Heritage team, completing a series of 360-degree panoramic photos, as well as 3D photographs of the Wynnum Museum.

“The 360-degree panoramas will enable online viewers to swivel the images on their screens to look around them as though they’re in the space,” Michael said.

“Each finished image uses about 50 individual photographs, all carefully aligned and having a secure central anchor point is important.”

Michael said he’d been learning about 360-degree panoramic photography and had studied the historical ambulances at Theodore to develop a workable plan to capture vehicle interiors.

“I decided to make myself a monopod with a bracket to prevent tripod legs intruding into an image,” Michael said.

But he admitted the 365-degree panoramic images of the Wynnum Museum’s interior were enormous productions.

“For example, the office photos were taken with the lights off, because all the surfaces were too reflective, so instead each individual photo had 30-40 second exposures.”

Michael said many additional hours of computer editing work were required to ensure a single seamless finished image.

“More often than not I’d need to go into a deep-dive into an image’s fine detail and develop some out of-the-box fixes which may have to be used across several individual images,” he said.

“Editing is required for each image and then again as a much larger image forms.

“For example, in one photograph I noticed a bottle of cleaner which had to be removed.

“I did this by accessing other images and rebuilding the photograph without this bottle of cleaner being evident.

“The 3D photographs were far simpler to produce – largely using two images taken a nose-width apart – and they are reasonably accessible, and people are more familiar with them.”

“The 3D photographs were far simpler to produce – largely using two images taken a nose-width apart – and they are reasonably accessible, and people are more familiar with them.”

Many of us grew up with a 3D viewfinder in the house – remember those red plastic devices you’d put your eyes up to with the rotating image discs to click through, or the cardboard or plastic spectacles with a blue and a red lens?

QAS History and Heritage Manager Mick Davis said over the past four years, the team has digitised and archived well over 100,000 images including digital donations, printed photographs, slides, and from news clippings.

He said the team was still going, and the total number of images in the collection will continue to grow, as additional images are added marking the news, people and places of our time.

“Our images and our visual history depict and illustrate the conditions, the uniform styles, vehicle presentations and utility and equipment, documents that were common at particular times in our history” Mick said.

“These visual presentations are of immense educational value for us and enable us to share our great history with our communities.”

Mick said he learned about Michael’s photographic skills at the Baralaba Station’s Centenary celebrations a few years ago and when Michael travelled to Brisbane for work last year, the team provided him with full access to the museum outside his rostered hours.

“These 3D and 365-panoramic images may be useful both on the QAS Heritage website and on screens in our four museum sites.

“It also means, for example, our visitors will still be able to view and appreciate an interior image of the cars, during the times when they’re not accessible.”

Mick said while the team has had some 360-degree videoing of the three museums and displays over recent years, this was the first time they’d been produced in image form.

Michael’s famous family connection with photography

Photography is in Michael’s blood – he’s a third-generation photographer and picked up a camera as a six-year-old and has barely put it down since.

“My grandfather, Alan Board, was an amateur photographer and when I was a kid, he taught me the basics, and inspired my interest in photography.

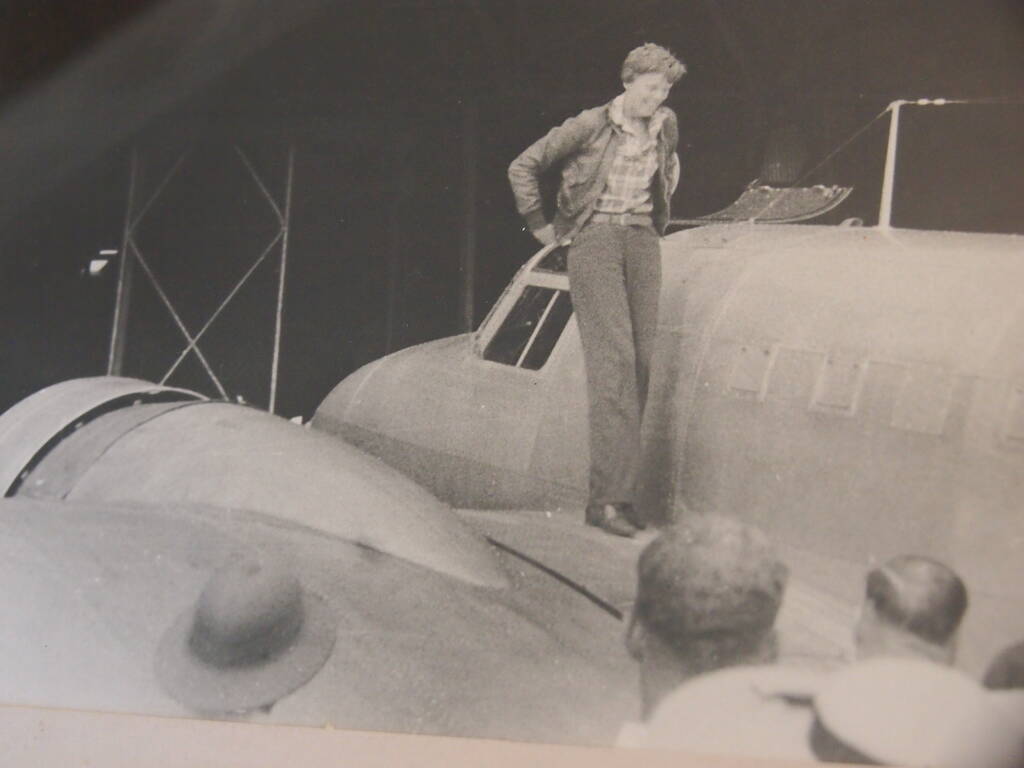

“He also took one of the last photos of the famous American aviator Amelia Earhart before she disappeared.”

During the 1920s and 30s, Earhart gained fame for her many piloting feats, making history for many solo flight “firsts” as an aviatrix.

But in 1937, during her attempt to fly around the world in her twin-engine Lockheed Electra with navigator Fred Noonan, the plane disappeared between Lae in New Guinea (as it was then known) and Howland Island.

Michael’s grandfather had his Leica camera with him to document Earhart’s refueling stop at Lae Airfield, snapping the pair as they loaded and completed their final checks before boarding their plane and taking off for the last time on their ill-fated flight.

“My grandfather told me about his memories of that day when I was a teenager,” he said.

“He said the fuselage was loaded from the floor to almost the ceiling with supplies, mostly fuel, and she [Earhart] had to crawl over the top of the boxes to get into the cockpit.

“The runway had been built right to the edge of the bay with the water below it, so the planes took off directly out over deep water.

“But when Earhart’s plane took off, he said it was so heavy and slow, it dipped where the runway fell away over the ocean, its wing tips were flexing and touching the ocean and the propeller was spraying water out over the wings," Michael said.

“My grandfather said he saw the plane travelling just above the waterline, until it reached the horizon where it slowly started to rise.

“He said he and the other onlookers there that day all had grave fears for the pair, and he wasn’t surprised later when he heard later on of their disappearance.”

Michael said at that time cameras were still relatively rare, so his grandfather often sent images he’d taken to Australian newspapers for publication, which was likely how some of these final images of Earhart had become famous.

“When I was a kid, my grandfather taught me photography on his much older, pre-war camera, which had no sensors or light meters, so I had to record the picture settings like aperture, speed and ISO, on paper to compare the images’ success after I’d developed them.

“I learned by trial and error and later learned to take portraits, landscapes as well as some of the early photographic tricks like making ghosts.”

In 1984, after leaving school, Michael purchased a second-hand Nikonos III underwater camera and spent some time diving and photographing Morton Bay.

As time brought significant technological changes to photography, Michael continued to develop his skills into the digital world.

Outside his QAS shifts, Michael completed a Masters of Entomology, putting his then newly developed micro-photographic skills to good use.

Michael said his most recent project at Wynnum Museum has enabled him not only to hone his 360-degree and 3D skills but will also enable a different viewing experience of QAS’s history in future.